Somewhere in the Preaching Christ in a Postmodern World series of talks (available on iTunesU), Tim Keller offers a brilliant fourfold schema that can help Christian academics to engage with our disciplines in a God-honouring and constructive way. Keller unfolds the schema as a way of understanding and engaging with culture in general, but I have found it useful as a way of feeling myself into my discipline. I reconstruct it here from memory and from my notes.

The schema is taken from 1 Corinthians 1:17-25:

For Christ did not send me to baptize but to preach the gospel, and not with words of eloquent wisdom, lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power. 18 For the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. 19 For it is written, “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart.” 20 Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? 21 For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, it pleased God through the folly of what we preach to save those who believe. 22 For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, 23 but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, 24 but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. 25 For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men.

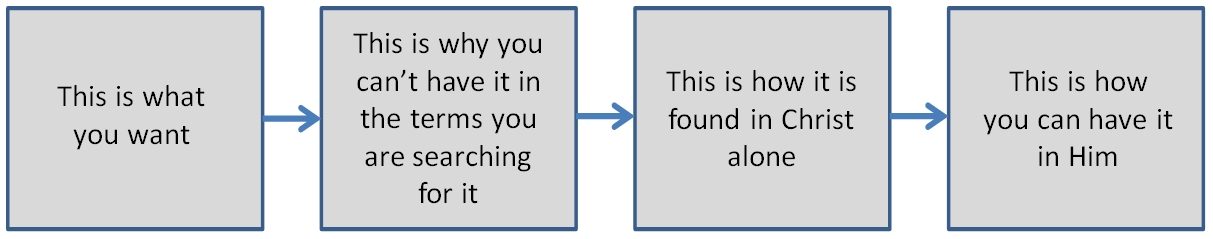

Keller discerns four moments in Paul’s analysis of Greek and Hebrew culture.

- This is what you want: Each culture has a value, something it seeks and esteems. For Jews it is divine power (in the form of miraculous signs), and for Greeks it is wisdom (in the form of philosophy).

- This is why you can’t have it in the terms you are searching for it: But each culture is cutting itself off from the very thing it seeks by looking for it in the wrong places. The Jews refuse to countenance the possibility of an agitating and inconvenient religious outsider having any ultimate clout with God, and the Greek search for wisdom is too narrowly focused and refuses to question its own constricting assumptions. The Jews could never accept a crucified messiah, even if this were God’s brilliant plan. If there were a wisdom from God in Christ, the Greeks could never know it, shackled as they are to the presuppositions entailed in their philosophical approaches. (I remember Keller being better on this point than I can reproduce here. I think he used an example from Albert Camus in a really helpful way. Post in the comments if you can remember what he said!)

- This is how it is found in Christ alone: This third moment is both a tragic and a delicious paradox. The irony in the situation of both the Greeks and the Jews, in Paul’s analysis, is that the very thing they seek is to be found only in the very one they despise. The Jews see in Christ a stumbling block, a weak and politically manipulable rabbi unable to save himself from an ignominious and accursed death. And the Greeks see in Christ a rather backward-thinking yokel (what do you expect from the University of Nazareth!) whose followers blather on crudely about the resurrection of the body. And yet it is in union with this renegade rabbi that we can encounter the universe-sculpting and sin-erasing power of almighty God as nowhere else; and it is in the vulgarity of the cross (how backward, blood-soaked and barbarous!) that we see the wisdom of God’s ultimate plan to “be just and the justifier of the one who has faith in Jesus” (Romans 3:26, my emphasis). There is no power to rival this, and there is no wisdom to rival God’s wisdom as it is revealed in Jesus, for “the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men”.

- This is how you can have it in Him: And so (verse 23) “we preach Christ crucified”. Not as a rival to the deepest desires and concerns of Greek or Hebrew culture, but as their one true fulfillment. What we ask is not that our culture and our disciplines start wanting different things, but that they swallow their pride and accept that they might find those things in what for them is the unlikeliest of places.

In the light of this passage, part of the task for Christian scholars is carefully to discern the values of the cultures of research in which we work, see how those values can only ultimately be satisfied in a Christ who paradoxically seems to offer their opposite, and then hold out Christ not as the enemy of all that our colleagues and our disciplines hold dear, but as the only hope of seeing those treasured values realised.

If you would like to read an example of how this schema can shape an approach to a thinker or to a discipline, I used it as an overarching framework to structure my book on Foucault.